A “search hedge” is a library term that describes one of two things:

- Filter: A pre-set feature found in some literature databases, that enables the user to be guided through a process to locate articles on a specific type of question.

- Hedge: A published (and sometimes validated) comprehensive search strategy for a database on a specific concept or topic, that can be added to a search, customized, or used as a complete ready-made search.

Search Filters

Search filters are found within a database and work by assisting the user with locating articles for a specific type of question by filling out a form/selecting a pre-set filter.

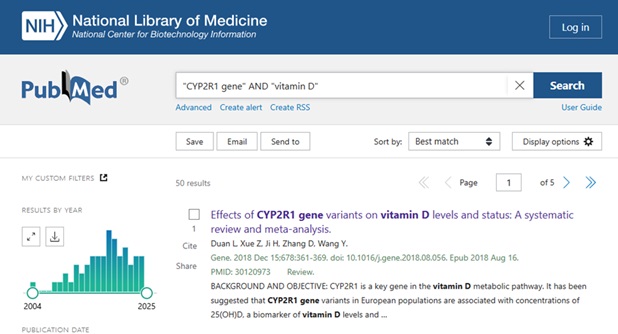

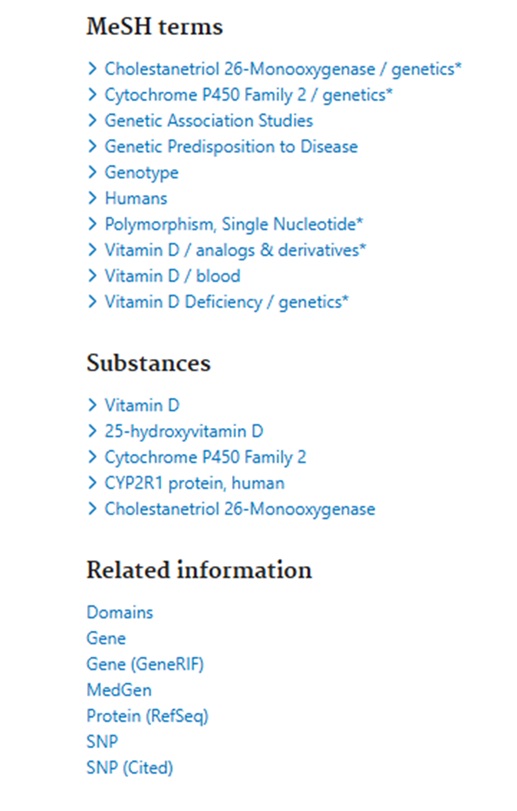

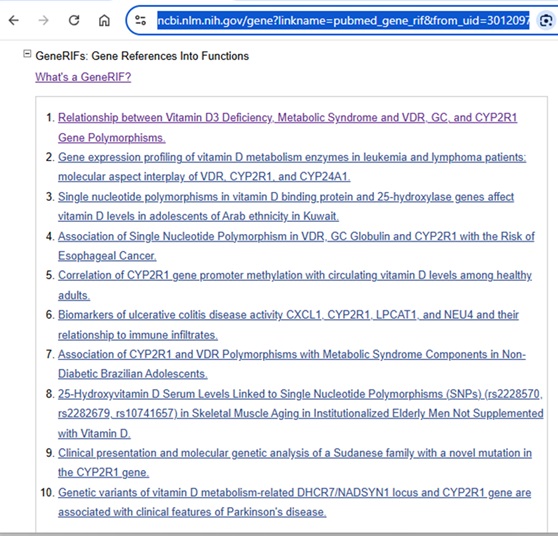

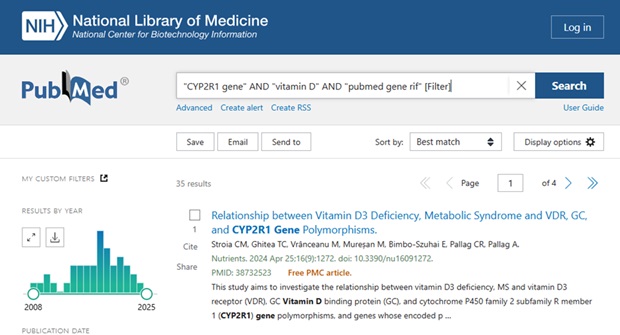

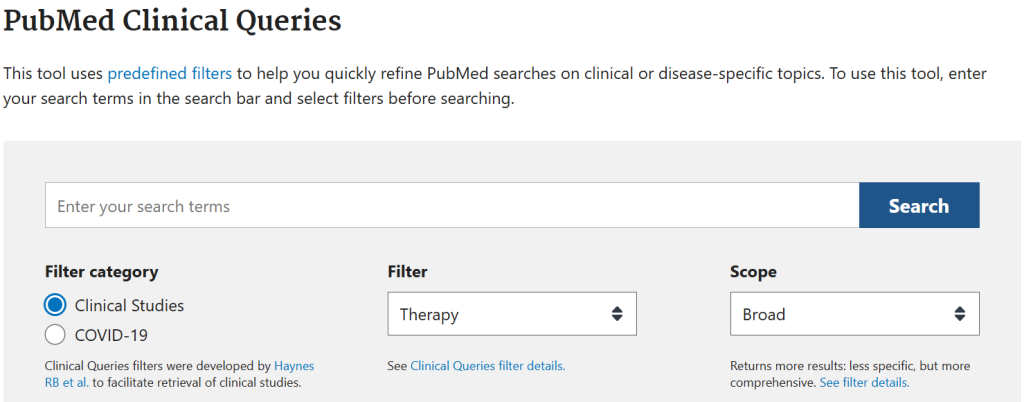

PubMed Clinical Queries

PubMed Clinical Queries are a built-in search hedge found in PubMed, that assists users in locating clinical studies to answer clinical questions. Users simply enter their search terms and answer several questions (such as whether the question is related to diagnosis, therapy, prognosis, or etiology), and from there PubMed adds a pre-set hedge that is designed specifically for the answers provided.

The search hedge itself is “hidden” from the search strategy seen by the user, however the complete hedge can be viewed in the Clinical Queries filter details.

Embase Search tools

When using Embase (on the Elsevier platform) there are several built-in search tools available to help quickly filter results when searching on specific topics, including: PICO, PV Wizard, and Medical Device.

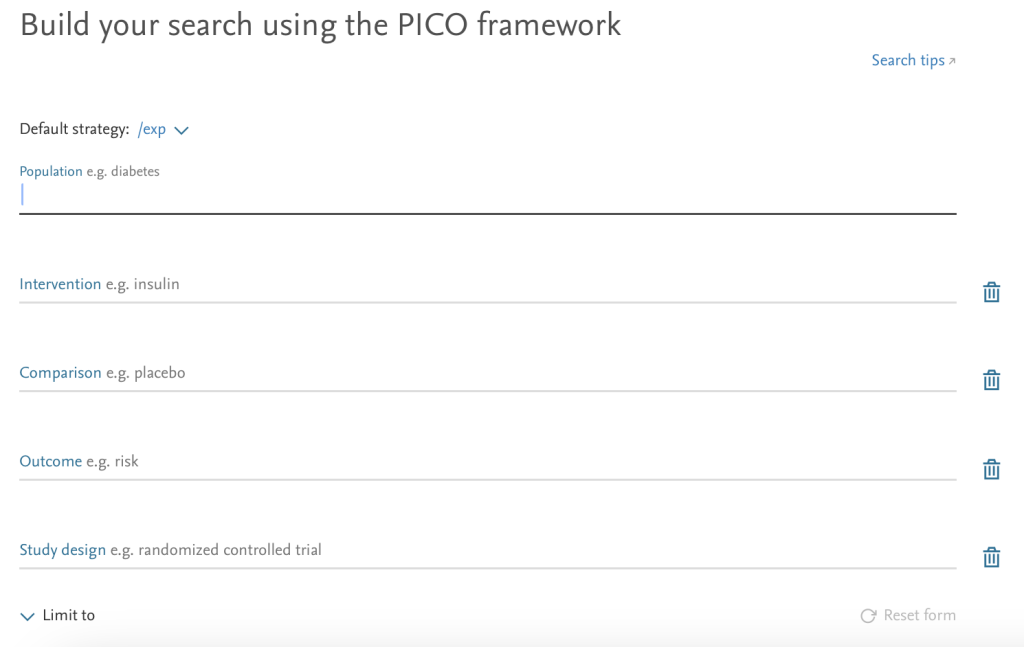

PICO

The PICO search tool assists in doing evidence-based practice by providing separate sections to enter each component of the PICO framework (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) as well as study design, to quickly identify clinical studies to answer the clinical question being addressed.

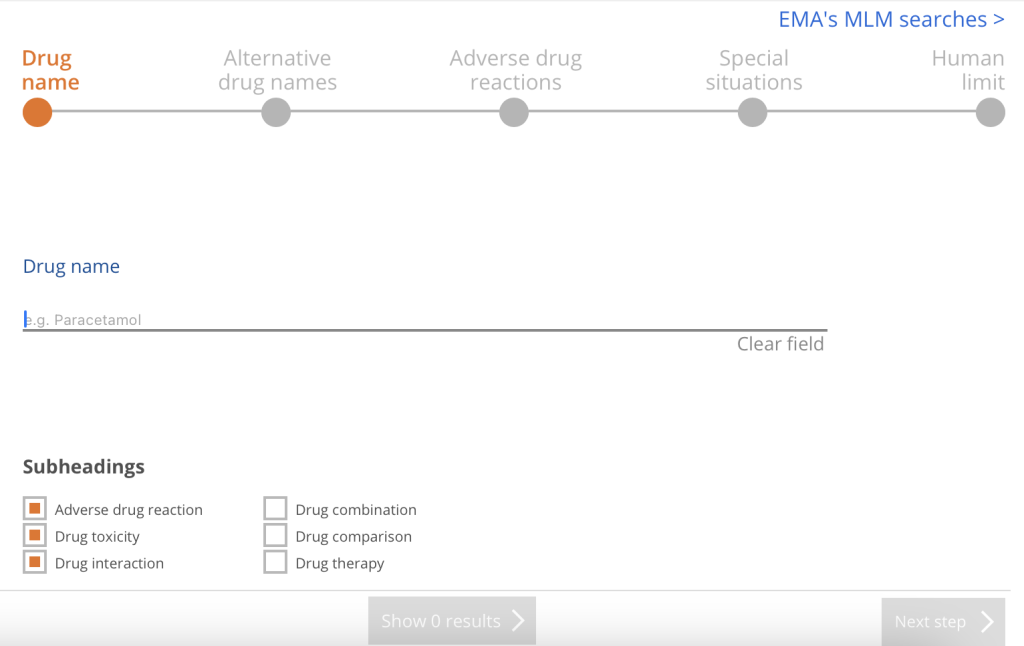

PV Wizard

The PV Wizard (PV stands for pharmacovigilance) allows the user to locate articles that address drug monitoring and adverse events using specific drug names (including trade, generic, and alternate names), with buttons to limit to things like adverse reactions, drug interactions, drug combinations, as well as special situations (pregnancy, breastfeeding, pediatric, geriatric, organ failure, etc.).

Medical Device

The Medical Device search allows users to quickly locate clinical and pre-clinical studies on general and medical devices, including manufacturers information and adverse events. This search hedge was developed and validated by industry representatives to ensure that it aligns with best practices for medical device monitoring.

Embase Quick Limits

Embase has several “quick limits” which are essentially search filters that can be added using a single click. These limits can be added by either checking off a box or by adding a specific field code to your search strategy.

- Humans: Either the Humans quick limit button or the field code [humans]/lim

- Animals: Either the Animal quick limit button or the field code [animals]/lim

- EBM: Quick limit button for Cochrane Reviews, Controlled Trials and RCTs

Search Hedges

Search hedges are comprehensive search strategies for a specific database on topics or concepts that have been devised by librarians or information professionals. These hedges are published and available for anyone to use, and many are also validated. While hedges can be used on their own, as ready-made searches on various topics, they are most often added on to the user’s search strategy to limit or narrow the results.

Most search hedges are designed for things like specific populations, study types, diseases or conditions, or outcome measures. Typically a search hedge can simply be copied and pasted into the database, and then using the Boolean operator AND, added to a search already created.

Embase Study Type Hedges

The Embase Study Type Hedges are standardized search strategies for common and frequently used concepts that can used along with a search query. These search strategy hedges can be copied and pasted into the search box in Embase and then added to an already designed search using the Boolean operator AND.

These hedges are to be used to focus on locating specific types of clinical or experimental studies, and each hedge has an option for either sensitivity (comprehensive) and specificity (focused) based results.

There are several types of hedges available on Embase.com.

- General Study Types: Therapy, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Etiology, Economics, etc

- Hedges by Topic: Diabetes, Real-World Data, Cost Effectiveness, DEI

- Animal Breed Hedges: Species-specific hedges for most animals used in research and agriculture

Locating Search Hedges

Since search hedges are published search strategies on specific topics, they can be found in a variety of places online. Some, such as the Study Type Hedges in Embase and the Study Type Filters in PubMed, are available from the database itself. Others can be found on various library websites, published literature, and in special search hedge repositories (though these may not be validated).

It’s common to find search hedges in systematic review resources, since systematic reviews require comprehensive search strategies, and search hedges can provide just that.

A validated search hedge is the “gold-standard” and has been independently tested and verified, so if there is a validated hedge available for the topic you are looking for, that is your best option.

Search Hedge Sources

- Canada’s Drug Agency (formerly Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health [CADTH]): Search Filter Database

- McMaster Health Information Research Unit (HIRU): Hedges Project

- InterTASC Information Specialists Sub-Group (ISSG): Search Filter Resource

- University of Alberta: Health Sciences Search Filters

- Library of Search Strategy Resources (LSSR): Collections

- CABI Digital Library: SearchRxiv

Suggested Reading

What is the difference between a filter and a hedge?. J Eur Assoc Health Info Libr [Internet]. 2016 Apr. 1 [cited 2025 May 6];12(1). Available from: https://ojs.eahil.eu/JEAHIL/article/view/95