The amount of published biomedical literature has been growing exponentially for decades, and that trend is not slowing down anytime soon. With this explosion of published content, it can be overwhelming to find exactly what you are looking for.

The 21st Century Digital Age

The start of the 21st century was heralded as the “digital age”, and the growth of content shifted from a linear to an exponential growth model. There were approximately 13 million citations in PubMed at the start of the 21st century. Within the first decade that number rose to 20 million. Today there are over 36 million citations in PubMed.

Source: Lu Z. PubMed and beyond: a survey of web tools for searching biomedical literature. Database (Oxford). 2011;2011:baq036. Published 2011 Jan 18.

Zhiyong Lu, from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), wrote about going beyond PubMed back in 2011, and shared an initial overview of web-based tools available that work alongside or on top of PubMed to provide more search functionality to users.

From the Digital Age to the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Today, as we now inch closer to the quarter-century point, digital technology has literally begun taking on a life of its own. With the advent of machine-learning and generative artificial intelligence, suddenly technology itself can create its own content! And while there are plenty of ethical issues surrounding the use and abuse of AI that cover nearly all aspects of life, this technology allows for considerable benefits as well.

New tools have emerged to help us better navigate, digest, and synthesize the overwhelming amount of digital information available, including biomedical literature. Many of these tools are web-based resources that either overlay or work in conjunction with PubMed to provide functionality that goes beyond basic search and retrieval.

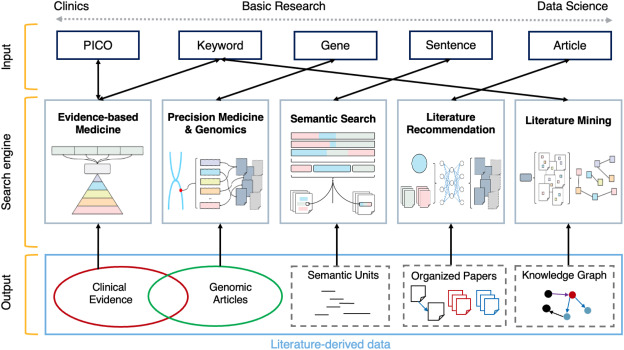

Last month, Zhiyong Lu and several of his colleagues from NCBI published an update to his 2011 overview; PubMed and beyond: biomedical literature search in the age of artificial intelligence. This update focused on how user search needs have expanded and AI tools can provide search functionality to address these different needs.

Source: Jin Q, Leaman R, Lu Z. PubMed and beyond: biomedical literature search in the age of artificial intelligence. EBioMedicine. 2024;100:104988.

They looked at five specific types of specialized search needs, and addressed the various tools and resources that can provide necessary functionality to support those search needs: evidence-based medicine, precision medicine, semantic searching, recommendations, and text mining.

Harness Technology with these Search Tools

Using these five identified search needs categories, below are selected resources to assist users in navigating and digesting the ever-expanding field of biomedical research.

Evidence-Based medicine

| PubMed Clinical Queries | This PubMed tool uses predefined filters to help you quickly refine PubMed searches on clinical or disease-specific topics. |

| Cochrane Clinical Answers | CCA provides readable, digestible, clinically focused actionable point-of-care information directly from Cochrane Reviews. |

| Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) EBP Database | The JBI EBP Database provides the latest research and evidence-based guidelines regarding patient care, treatment options, and interventions to empower clinicians and healthcare administrators to make informed, confident decisions. |

| TRIP Database | TRIP is a clinical search engine designed to allow users to quickly and easily find and use high-quality research evidence to support their practice and/or care. |

Precision Medicine & Genomics

| OncoSearch | OncoSearch is a text mining search engine that searches Medline abstracts for sentences describing gene expression changes in cancers. |

| LitVar | LitVar normalizes different forms of the same variant into a unique and standardized name so that all matching articles can be returned regardless of the use of a specific name in the query. |

| DigSee | DigSee is a text mining search engine to provide evidence sentences describing that “genes” are involved in the development of “disease” through “biological events”. With a query of (disease, genes, events), Medline abstracts with highlighted evidence sentences will be retrieved. |

Semantic Searching

| LitSense | LitSense is a unique search system for making sense of the biomedical literature at the sentence level. Given a query, LitSense finds the best-matching sentences based on overlapping terms as well as semantic similarity via a cutting-edge neural embedding approach. |

| AskMEDLINE | Search PubMed using free-text and natural language |

| BioMed Explorer | BioMed Explorer applies semantic understanding of the content of the papers to pull out answers and highlight snippets and evidence for the user. |

| Semantic Scholar | Semantic Scholar provides free, AI-driven search and discovery tools, and open resources for the global research community. |

Literature Recommendations

| LitSuggest | Advanced machine learning and information retrieval techniques are utilized for finding and ranking publications pertinent to a topic of interest. |

| Connected Papers | Connected Papers is a unique, visual tool to help researchers and applied scientists find and explore papers relevant to their field of work. |

Text Mining

| PubTator | PubTator Central (PTC) is a Web-based system providing automatic annotations of biomedical concepts such as genes and mutations in PubMed abstracts and PMC full-text articles. |

| PubMedKB | PubMedKB combines a multitude of state-of-the-art text-mining tools optimized to automatically identify the complex relationships between biomedical entities in the PubMed abstracts. |

As technology evolves, so will the research environment, and it’s imperative that we are able to leverage technology to keep up. It’s also important to understand these new technologies, how they work, and how they can be used to make work more efficient. But it’s also important to understand their limitations and the ethical issues that could arise when using these technologies without further human insight.

A new eBook has been added to the MSK Library collection,

A new eBook has been added to the MSK Library collection,