Understanding the extent to which a particular database indexes the contents of a journal is a crucial step towards maximizing the visibility and reach of your published work(s).

Although social media and other marketing channels have definitely helped with getting the word out about new research in scholarly publishing, the reach of bibliographic indexes in terms of providing access to content beyond an individual author’s personal and professional networks is still very significant.

There are a few factors that impact the visibility and reach of a literature database:

1) Public access versus commercial databases

Content that everyone has access to because it is not stored behind a paywall, regardless of how well-funded their institution is or if they are affiliated with a research library or not, has the potential of reaching a wide range of audiences across the globe. In the case of PubMed, for example: “On an average working day approximately 2.5 million users from around the world access PubMed to perform about 3 million searches and 9 million page views.”

2) Syndicated/leased/shared versus proprietary content

“Syndicated content is content that is published on multiple sites beyond the source, which broadens its reach and visibility”. There are some databases, like MEDLINE, whose content is leased to other database vendors and can be searched (in whole or in part) in other resources. For example, MEDLINE content is included in EMBASE, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library. Having a journal indexed in both MEDLINE and PubMed, therefore, increases the potential for the contents of that journal to be discovered by searchers of databases beyond NLM’s PubMed’s free search interface. For this reason, it is helpful to understand the difference between PubMed and MEDLINE and how each of these resources is put together.

3) “Surface” versus “deep” web indexing by search engines

Another important question to ask of an online database is: Do regular web search engines, like Google, “see” the contents of this database? In the case of the vast majority of database resources on the Internet, the standard World Wide Web search engines generally stop at the front door of the database tool and do not index the actual contents within the database. In the case of PubMed, however, Google actually “crawls” the records contained within the database, increasing their findability by Google Scholar searchers who may never search the PubMed database via its native interface.

From Vine R. Google Scholar. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Jan;94(1):97–9. PMC1324783:

“Much of Google Scholar’s index derives from a crawl of full-text journal content provided by both commercial and open source publishers. Specialized bibliographic databases like OCLC’s Open WorldCat and the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed are also crawled. Since 2003, Google has entered into numerous individual agreements with publishers to index full-text content not otherwise accessible via the open Web. Although Google does not divulge the number or names of publishers that have entered into crawling or indexing agreements with the company, it is easy to see why publishers would be eager to boost their content’s visibility through a powerhouse like Google.”

In short, selecting a journal to publish in that is indexed in PubMed, as well as, in MEDLINE, gives your manuscript a good head start towards achieving maximum international reach and visibility.

Follow these steps to determine whether a journal is indexed in PubMed alone, in both PubMed and MEDLINE, or in neither:

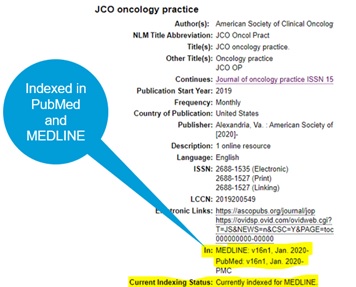

Click on the “Journals” link of the PubMed homepage or go directly to the NLM Catalog to search for Journals referenced in the NCBI Databases. Once you bring up a catalog record for a journal of interest, click on the title to open the full record where you can confirm a journal’s MEDLINE “Current Indexing Status”.

Below are examples of the indexing status information provided in NLM Catalog records:

- Journal indexed in both PubMed and MEDLINE: JCO Oncology Practice

- Journal indexed in PubMed only: NPJ Breast Cancer

- Journal NOT indexed in PubMed or MEDLINE: JCO Precision Oncology

Questions? Ask Us at the MSK Library!