Over the last decade, many in the scholarly research community have been sounding the alarm about journal article retractions being on the rise, for example:

- Else H. Biomedical paper retractions have quadrupled in 20 years – why? Nature. 2024 Jun;630(8016):280-281. doi: 10.1038/d41586-024-01609-0. PMID: 38822109.

Most prominent of these voices has been Dr. Ivan Oransky, co-founder of the Retraction Watch Database:

- Oransky I. Retractions are increasing, but not enough. Nature. 2022 Aug;608(7921):9. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-02071-6. PMID: 35918520.

Thanks to an increase in awareness of this issue, new technologies have been developed to help alert library discovery tool users whenever they come across retracted items while searching. The thinking is that researchers should have the opportunity to closely examine retracted publications – and even publications that cite retracted papers but are not retracted themselves – as the research being reported within them may be compromised in some way.

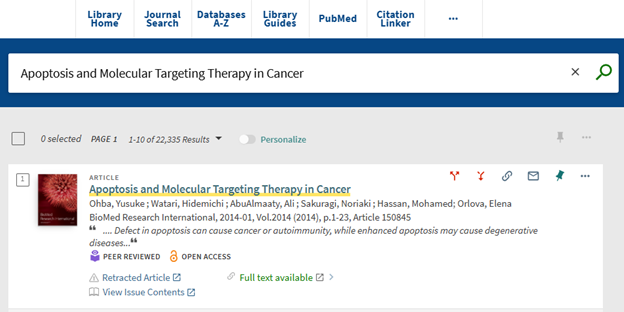

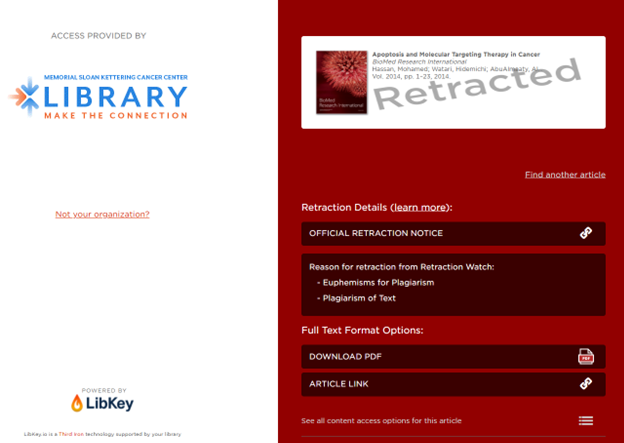

One such tool, LibKey, that MSK community members can use via the library’s OneSearch catalog, flags retracted article citations whenever they appear in search result lists – see:

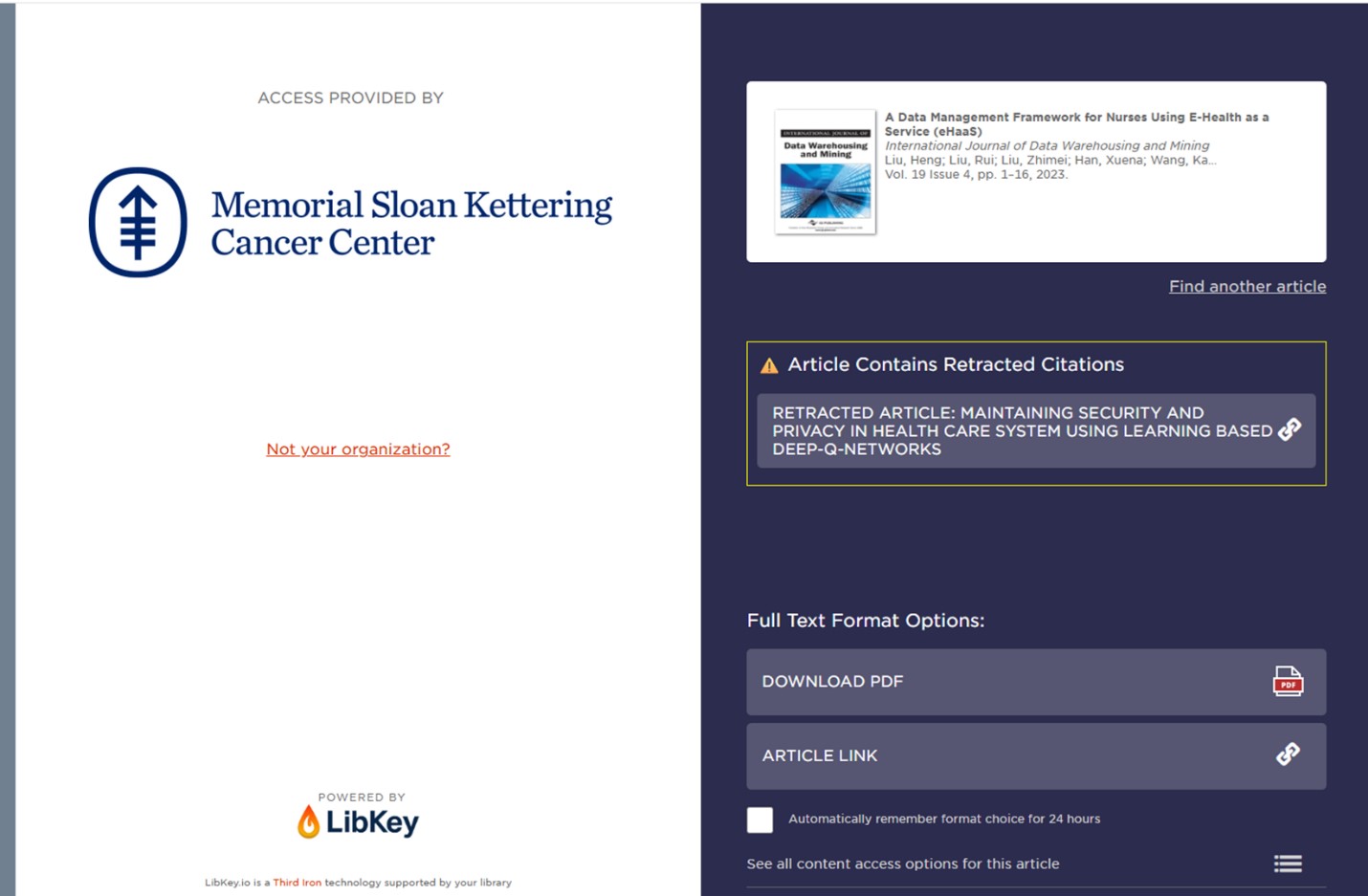

Starting in Summer 2025, LibKey expanded its retraction notification capabilities to also include “data about articles which cite one or more retracted articles”.

As per the LibKey (Third Iron) vendor’s newsletter:

“If a paper cites one or more retracted articles, LibKey will display an interstitial screen indicating which citations have been retracted”.

For example – see:

If you have any questions or want additional guidance related to retractions, checkout “About Article Retractions” or feel free to Ask Us at the MSK Library.