Thanks to recent current events, plagiarism has suddenly become a very hot topic in the news media. Understandably, scholarly authors from across all disciplines are likely asking themselves the question: “Is my risk of being accused of plagiarism zero percent?”

Below are actions that you should be taking to mitigate your risk of plagiarizing:

- Select a citation manager, become proficient at using it, and – most importantly – use it!

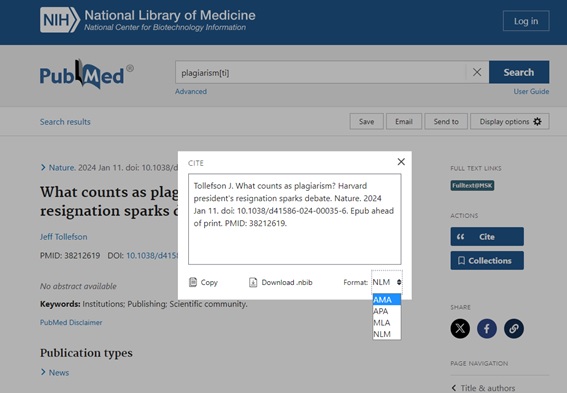

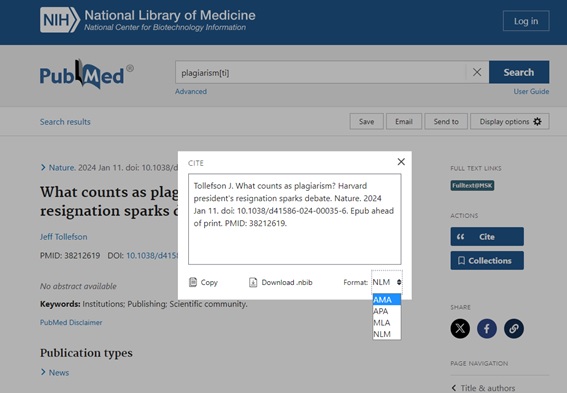

With so many citation manager options available for researchers with vastly different habits and preferences, there is no excuse not to use one to help make citing sources of information automatic and a breeze for you to do. Explore the “Choosing a Citation Manager” tab of the MSK Library’s Citation Management LibGuide to make sure you are using the tool that best matches your needs and take advantage of training options listed under the Tutorials tab. Another action you may wish to consider is to try a browser add-on (or browser extension) that can help better integrate the capturing of citation information and PDFs into your online researching workflows. Many citation managers – and even other search tools like Google Scholar – now offer such tools. Finally, for those not working on devices that are set-up to easily export citation record files, many literature databases and scholarly publisher websites make it possible for readers to preview an individual reference formatted according to a particular citation style that can be copied and pasted into a word processor.  Screenshot from PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212619/

Screenshot from PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212619/

- (Re-)Familiarize yourself with the evolving definition of what constitutes plagiarism.

Getting everyone to agree on the definition of plagiarism, the severity of the plagiarism, and how to handle it, is trickier than you might expect, especially if the plagiarism in question could potentially spill over into retraction and research misconduct territory. Many scholarly publishers provide detailed guidance for their authors about what they consider to be plagiarism and how they handle cases where it is detected (for an example, see Taylor and Francis Author Services).

One type of plagiarism that, although considered to be less severe by most – causes a lot of headaches for many authors in the text-matching software era, is self-plagiarism. Excessive self-citation has been villainized so much in recent years, that authors are often reluctant to include citations to their own past works – even when it is fully warranted – for fear of being accused of unethical publishing behavior by their peers. What they don’t realize, however, is that excluding self-references then puts them at a higher risk of being accused of plagiarism, arguably the offense that can have graver reputational consequences. Open access (OA) publishing may also have contributed to the confusion around self-plagiarism, with some authors assuming that, having not transferring their copyrights to the publisher in the traditional way, they are free to re-use their own past paper’s phrasing without conditions (like having to quote themselves and cite their own work). Even though they may have kept their copyrights, however, most (OA) journal Creative Commons licenses are at least CC-BY, meaning that the publisher still requires that “credit must be given to the creator,” even if the creator is yourself! Another self-plagiarism/text recycling grey area that has emerged in recent years involves duplicate publication in the preprint era as scholarly publishers preprint policies can vary.

- Take proactive steps to make sure you have not inadvertently broken some rules before submitting your papers for official publication and/or grading (if you are a graduate student).

Authors who submit papers for publication in biomedical journals should expect that part of the manuscript submission process in 2024 will likely involve their manuscript being checked for plagiarism and for being a duplicate submission. To protect themselves, many publishers (for example, Elsevier) use the Crossref Similarity Check Service to automatically check all new submissions. From https://www.elsevier.com/editor/perk/plagiarism-complaints/plagiarism-detection:

“In 2008, Crossref and the STM publishing community came together to develop Crossref Similarity Check, a service that helps editors to verify the originality of papers. Crossref Similarity Check is powered by the iThenticate software from iParadigms, known in the academic community as providers of Turnitin.”

Even though many publishers likely use the same plagiarism detection tool, they may differ from one another in how their editors interpret and deal with high similarity scores. If plagiarism is suspected, authors might be given the opportunity by some publishers to make corrections and add needed quotation marks or missing references to the manuscript. Other journal publishers, on the other hand, may take more of a “one strike and you are out” approach, especially if it is a journal with a high rejection rate that is generally overloaded with manuscript submissions. MSK authors can completely avoid this risk by taking advantage of the MSK Library’s institutional subscription to iThenticate which allows them to personally, pre-emptively check their own work for plagiarism in advance of actually submitting their manuscript to a journal for publication.

- If you supervise trainees, make sure that their MSK experience includes some library training and other types of authorship support. (eg. manuscript editing, language translation services, etc.)

The MSK Library offers a wide array of training classes that can directly or indirectly help researchers avoid carrying out plagiarism. Apart from teaching how to use citation management software, librarians teach workshops on topics like “Measuring Research Impact” that discuss the outcomes of citing the work of authors and giving proper credit in the scholarly publishing ecosystem. Trainees who fully appreciate the important role of citation analysis for establishing research impact will generally be more careful about making sure to cite the work of others when appropriate and will expect that their own work be correctly cited when discussed by other authors.

Questions? Ask Us at the MSK Library!

Screenshot from PubMed:

Screenshot from PubMed: