As ClinicalTrials.gov celebrates its 25th anniversary, reaches its half-million registered studies milestone, and completes its modernization, it’s a good time to appreciate this invaluable research tool that has been around since 2000. In 2008, NLM launched the ClinicalTrials.gov results database, which now (as of 12/2024) has >70K registered studies posted with results.

Openly available to all with “about 90 thousand visitors per day and 2 million unique visitors every month”, ClinicalTrials.gov is a registry where individuals can identify both ongoing and completed registered trials from “50 States and in 229 countries and territories”.

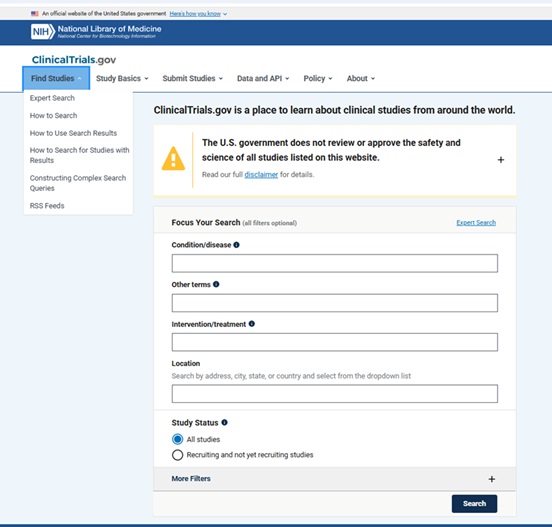

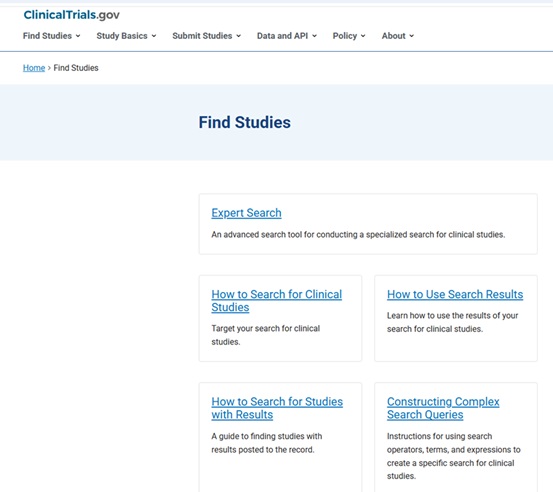

Some functionality that has been added over the last few years (related to how you can search the database using Complex Search Queries and how you can download and use the search results/records from ClinicalTrials.gov) has made this database increasingly attractive as a data source for answering research questions.

From: https://clinicaltrials.gov/find-studies

In addition to having search functionality that allows for very precise searching, it is now possible to download search results from ClinicalTrials.gov in the RIS file format that can be imported into citation management tools like EndNote and Covidence (used for managing systematic review projects).

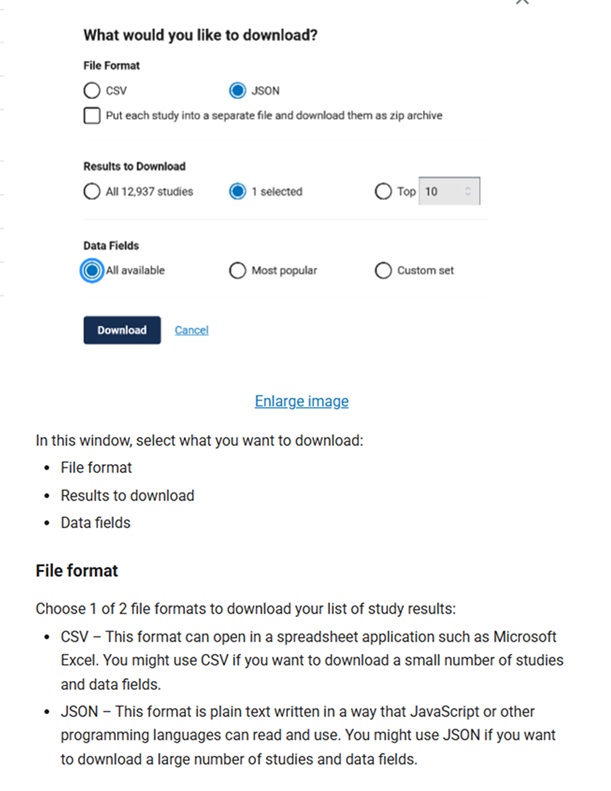

It is important to note that the data fields included in the RIS download (which is not customizable), differ from those included in the CSV file download data fields (which a user can select from a menu of options), which differ from the JSON format (which can include every available data field for each study being downloaded). The ClinicalTrials.gov API option allows the ClinicalTrials.gov database to be accessed on a large scale, automated way by researchers and developers.

From: https://clinicaltrials.gov/find-studies/how-to-use-search-results

Examples of research projects that have leveraged ClinicalTrials.gov data:

- Alhajahjeh A, Rotter LK, Stempel JM, Grimshaw AA, Bewersdorf JP, Blaha O, Kewan T, Podoltsev NA, Shallis RM, Mendez L, Stahl M, Zeidan AM. Global Disparities in the Characteristics and Outcomes of Leukemia Clinical Trials: A Cross-Sectional Study of the ClinicalTrials.gov Database. JCO Glob Oncol. 2024 Nov;10:e2400316. doi: 10.1200/GO-24-00316. Epub 2024 Dec 2. PMID: 39621951.

- Chen D, Parsa R, Chauhan K, Lukovic J, Han K, Taggar A, Raman S. Review of brachytherapy clinical trials: a cross-sectional analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov. Radiat Oncol. 2024 Feb 13;19(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13014-024-02415-8. PMID: 38351013; PMCID: PMC10863227.

- Falade AS, Adeoye O, Van Loon K, Buckle GC. Clinical Trials in Gastroesophageal Cancers: An Analysis of the Global Landscape of Interventional Trials From ClinicalTrials.gov. JCO Glob Oncol. 2024 Aug;10:e2400169. doi: 10.1200/GO.24.00169. PMID: 39173083.

- Pearce FJ, Cruz Rivera S, Liu X, Manna E, Denniston AK, Calvert MJ. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in trials of artificial intelligence health technologies: a systematic evaluation of ClinicalTrials.gov records (1997-2022). Lancet Digit Health. 2023 Mar;5(3):e160-e167. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00249-7. PMID: 36828608.

- Yang A, Baxi S, Korenstein D. ClinicalTrials.gov for Facilitating Rapid Understanding of Potential Harms of New Drugs: The Case of Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Oncol Pract. 2018 Feb;14(2):72-76. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025114. Epub 2018 Jan 3. PMID: 29298113; PMCID: PMC5812307.

Questions? Ask Us at the MSK Library!